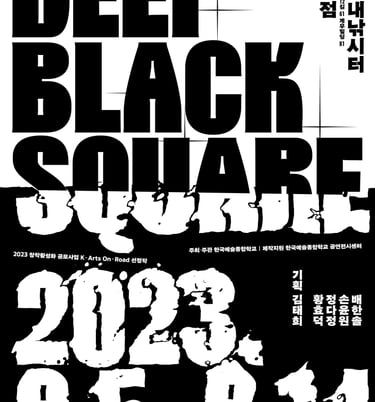

Deep Black Square

2023.09.05-09.14

Curator : 김태희 Kim Tae-Hee

Artists : 배한솔 Bae Han-sol @pinetreeboat

손윤원 Son Youn-won @younwon.s

정다정 Jeong Da-jeong @dajeong.jeong___i

황효덕 Hwang Hyo-duck @hwang_hyo

Texts : 생물학자 이동주 Biologist Lee Dong-ju @science_dongju

조류생태학자 최그린 Ecologist Choi Green @meetgreen.kr

Copyread : 양채원 Yang Chae-won

Location : 가자 실내낚시터 대학로점

Gaga Indoor Fishing Cafe Daehak-ro

TIME : 월-일 13:00-20:00 Mon-Sun 13:00-20:00

Photo/Video : 스튜디오 스택 @studio.stack

2023 창작활성화 공모사업 K-Arts on Road 선정작

2023 K-Arts on Road Open Call @karts_pe_center

바다를 고이 접어 간직할 수 있다면

김태희

“돌을 깨고 있는 사나이에게 다가가 물었다/ 아주 높은 설산 아래서였다/ 왜 물고기 화석이 여기 있지요? 그럼 우리도 바다로부터 건져 올려진 건가요? … 그래, 또 산에 오르게 될 것 같으냐고 물었어요/ 물론이라고/ 산은 우리가 미처 걸어서 건너지 못한 바다라고 말했어요“ ─ 이병률, 〈설산〉, 『바다는 잘 있습니다』, 2017, 문학과 지성사

전시는 실내 낚시터의 수조를 미래의 바다로 가정하고, 이를 ‘Deep Black Square (이하 ⬛)’라고 명명하는 것으로 시작한다. 후쿠시마 원전 오염수 방류가 초래할 결과가 시사하듯 바다의 앞날은 어둡다. 인류는 생물종이 사라지는 바다 앞에 서서, 바다의 일부분도 제대로 파악하지 못한 채 우두커니 서 있다. 바다 깊은 곳에는 우리의 상상을 뛰어넘는 생명체가 가득하다. 우리는 바다를 알지 못한다. 알지 못하기에 볼 수 없는 바다는 한 줄기 빛도 들지 않는 심연이다.

몇몇은 눈을 감고 바다를 바라보기도 한다. 거북이의 코에서 빨대를 끄집어내는 순간에도, 바다에 쓰레기 섬이 만들어질 때도 잠시 눈을 감는다. 더운 여름날 플라스틱에 담긴 얼음 컵과 음료를 외면하기는 어렵다. 바다 바닥까지 쓸어 담는 어획은 예상치 못한 수확을 가져다준다. 편리함과 경제적 대가를 마다할 사람이 몇이나 될까. 그러니 일시적으로 눈먼 채 바라보는 바다는, 아득히 검다. 실내 낚시터에서 물고기가 잘 보이지 않도록 수조에 푸는 검은 색소처럼.

생태계 파괴라는 필연적인 낙망. 이를 극복할 수도 있다는 우연에 기댄 희망. 누적된 과거로서의 현재. 축적된 현재 가 빚어낼 미래. 이 둘을 일시적으로 중첩하여 ⬛를 열어냈다. 미래의 바다가 현현된 검은 육방체에서 예술이 무엇을 할 수 있을까? 누군가는 기후 변화와 같은 여러 가지 환경문제가 인간이 손 쓸 수 있는 범위를 상회한다고 말한다. 그러나 단 몇 년이라도 에베레스트의 만년설이 녹아내리지 않도록 시간을 버는 것, 대기 중 배출되는 이산화탄소를 붙잡아 두는 것. 바다를 기억하고, 바라보고, 주목하는 것 역시 우리의 선택이다.

지구가 원판이라고 생각하던 시절의 바다는 둥그런 호를 따라 떨어지는 거대 폭포였다. 우주에서 지구를 바라보았을 때는 땅의 끝자락에 맞춰 바다의 모양이 결정되었다. 말하자면 바다는 육지에 선 인간의 입장에서 그려졌고, 육지의 모양에 맞춰 재단되었다. 우리는 육지에서 내려와 바다에 몸을 맡겼다. 깊이를 알 수 없어 칠흑 같은 망망대해를 항해했다. 네 명의 작가는 항해의 끝에서 무엇을 보았을까?

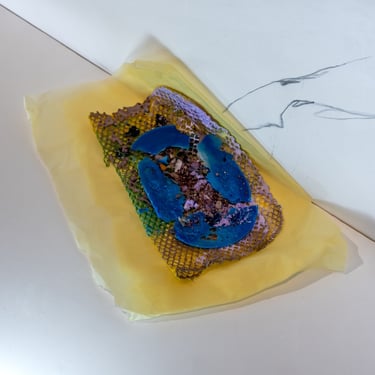

작년 늦여름, 정다정 작가와 함께 부산 국립해양박물관 벤치에 누워 하늘을 바라본 적이 있다. 그때 그녀가 바라보던 것은 하늘이 아니라 광활한 캔버스에 그려진 바다였던 것 같다. 정다정은 얼음에 하늘을 담아 바다를 상상하다가, 넓은 바다가 손바닥에 들어오는 크기가 될 때까지 멀찌감치 걸어 나간다. 그리고 바다를 접고, 구부리고, 때로는 도구를 만들어 바다의 일부를 수집한다. 손을 쭉 뻗어 바닷물을 휘휘 젓는다. 손가락 사이로 빠져나가는 바닷물의 감각을 기록한다. 긴 손잡이가 달린 양동이로 바닷물을 길어 한 모금 들이켠다. 바다를 접어 납작하게 만들었다가, 문득 바다의 넓이가 궁금해질 때면 접어둔 바다를 펼쳐 실 하나를 툭 던진다. 실은 바다를 가늠하기 위해 물결 따라 위아래로 출렁이며 바다의 모서리로 떠난다. 멀지만 가깝고 가깝지만 아득한 거리감은 지구와 달이 빚는 묘한 긴장감을 일깨운다. 바다에 건넨 종이컵 전화기에 귀 기울여 가느다란 실이 전하는 이야기에 집중할 때, 작가는 어슴푸레 떠오른 ⬛를 감각한다. 정다정의 태도는 바다와 우리가 느슨하지만 끈끈하게 연결된 관계임을 말해준다.

황효덕 작가는 바다 내음을 맡았던 기억을 떠올리며 호흡이라는 단위로 바다를 바라보았다. 먼저 작가는 잠수복을 입고 바다에 들어선다. 그리고 튜브에 바닷물을 담아 순환시킨다. 깊은 ⬛에 도달한 그는 하이드로폰을 가지고 물고기의 움직임이 만드는 진동을 소리로 변환하여 송출한다. 진동은 물고기의 생존 여부와 생명력을 알 수 있는 지표이다. 관객은 이 지표를 통해 물고기의 호흡을 가늠해 볼 수 있다. 작가는 ⬛의 물고기들이 상하 운동을 거의 하지 않는다는 사실을 발견한다. 이에 물고기의 상하운동을 조절하고 때때로 호흡을 돕는 부레를 제작하였다. 관객은 인간의 폐보다 훨씬 작은 부레로 직접 호흡하면서 숨이 가빠오는 경험을 하게 된다. 작가가 전하는 숨 가쁜 호흡은 ⬛ 속 삶의 터전을 위협받는 생명체의 숨소리이기도 하다. ⬛에서 잠수를 마친 작가가 수면위로 올라와 석호(潟湖)를 마주한다. 석호는 바다와 육지의 경계에서 형성되는 곳이자 바닷물과 담수가 교차하는 장소이다. 작가는 석호를 바라보며 바다의 숨결이 시작되고 끝나는 순간을 기록한다.

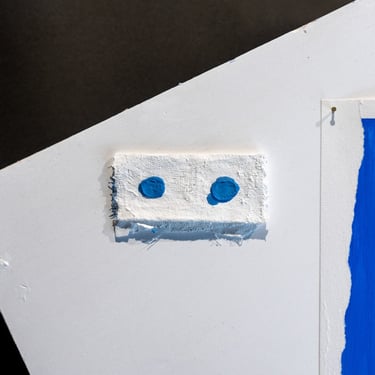

배한솔 작가가 마주한 ⬛는 선박 위치 추적 기술이 실제를 한발 늦거나 빠르게 추격할 때, 그 시차에서 드러난 지형이다. 그는 “Beyond Trust(진실 너머)”라는 이름의 배에 탑승했던 경험에서 작업을 시작한다. 작가는 배의 항로와 위치를 보여주는 “Marine Traffic(마린 트래픽)”이라는 어플리케이션으로 탑승한 배의 실시간 위치를 추적하게 되었다. 작가는 어플리케이션의 화면에서 가득 찬 수많은 배를 목도했지만, 하룻밤이 지나도 배를 마주치는 일은 드물었다. 실제 배의 위치와 어플리케이션 상 배의 위치 사이의 유격은 바다를 이해하는 현대 기술의 한계를 드러낸다. 작가는 기술적 한계가 드러난 ⬛에서 육지와 다른 방향감각을 기록한다. 육지는 지형이 고정되어 있고, 앞선 사람이 지나간 흔적이 남는다. 이를 통해 목적지로 향하는 위치와 방향을 찾는다. 반면 바다는 육지와 상황이 다르다. 예컨대 별이 보이지 않고 나침반이 고장 난 채로, 바다 위 작은 배에서 위치를 파악한다고 가정해 보자. 저 먼 바위섬, 화물선, 비행기와 나를 견주어 얼마간의 방향과 위치를 가늠해 볼 수 있겠다. 그러나 위치를 파악하기 위한 대상은 각각의 방향으로 멀어질 뿐이다. 따라서 배한솔이 포착한 ⬛는 우리의 위상이 언제나 상대적일 수밖에 없음을, 중심이나 구심점을 이뤘다면 이는 일시적인 상태임을 시사한다.

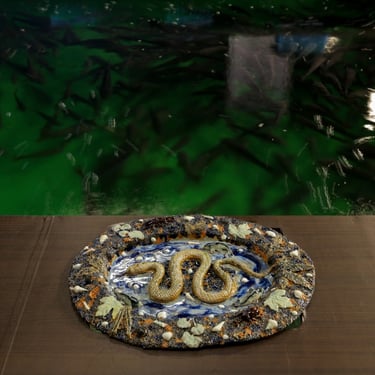

손윤원 작가의 ⬛는 유희나 취미의 대상이 된 물고기가 거주하는 공간이다. 작가는 이들을 위한 만찬을 플래터(Platter)에 담아 준비한다. 플래터는 접시로 번역할 수 있지만, 먹고 싶은 음식을 한데 모은 접시를 뜻하기도 한다. 각종 동식물이 담긴 플래터는 얼핏 보기에 지상낙원처럼 보이기도 한다. 손윤원은 이 플래터의 양식을 16세기 도예가 베르나르 팔리시(Bernard Palissy, 1510-1589)의 플래터에서 차용했다. 팔리시 양식을 차용하고, 인터넷에서 판매하는 복제용 몰드를 구입해 플래터를 장식하는 방식은 이전부터 조각을 다루는 작가의 태도이기도 하다. 학계의 의견이 분분하지만, 손윤원은 종교재판으로 생을 마감한 팔리시가 성경에 기초하여 뱀이 인간의 욕망을 상징하는 것으로 활용하였다고 보았다. 따라서 작가는 물고기에게 해가 되지는 않지만, 인간에게는 두려움을 심어주는 뱀을 플래터 한가운데 두어 물고기를 대상화하는 인간의 욕망이 타당한지 질문하고자 했다. 물고기의 먹이인 꼽등이와 갯지렁이는 수조에 가득 찬 물고기처럼 우글우글한 모습으로 플래터 밖 실제 공간에서 관객을 반긴다. 작가가 준비한 서늘한 만찬은 흙으로 빚어진 것이다. 죽으면 흙으로 돌아간다는 말처럼, 작가의 만찬은 ⬛안에 녹아 그저 작은 흙 알갱이로 돌아갈 뿐이다.

실내 낚시터에 들어서면 코에 닿는 비릿함이 관객의 삶 속에서 때때로 기억나길 바란다.

10년 뒤, 50년 뒤, 100년 뒤, 우리 서로 안부 인사를 건넬 수 있다면.

바다는 잘 있습니다. 라고.

If we could gently fold the sea and hold it close…

Kim Tae-Hee

"Approaching the man breaking rocks, I asked under a very high mountain / Why are there fish fossils here? So, are we also brought up from the sea? ... Yes, I asked if we would climb the mountain again / Of course, he said / The mountain said that the mountain is a sea that we could not cross"

- Lee Byung-ryul, "Snow Mountain," from "The Sea Is Fine," 2017, Moonji Publishing

The exhibition begins by assuming the indoor fishing tank as the future sea and naming it the "Deep Black Square (hereinafter ⬛)." As indicated by the consequences of the Fukushima nuclear plant's contaminated water discharge, the future of the sea is bleak. Humanity stands before a disappearing ocean, with parts of it not properly understood. Deep within the sea lie life forms beyond our imagination. We don't know the sea. Because we don't know, the unseen sea is an abyss without a ray of light.

Some close their eyes and gaze at the sea. Even when pulling out a straw from a turtle's nose or when a garbage island is formed in the sea, they close their eyes for a moment. It's hard to ignore plastic cups and drinks on hot summer days. The catch that sweeps down to the bottom of the sea brings unexpected harvests. How many are willing to forego convenience and economic costs? So, temporarily, the sea looked at blindly is profoundly dark. Like the black dye poured into the tank of the indoor fishing site, obscuring the fish.

Inevitable despair of ecosystem destruction. Hope leaning on coincidences that we can overcome it. The present as an accumulated past. The accumulated present shaping the future. By temporarily overlapping these two, ⬛ is opened. What can art do in the black cubic future sea? Some say various environmental issues like climate change exceed human intervention. However, even if just for a few years, to withstand the melting of the perennial snow on Everest, to hold onto the carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere. Remembering, looking at, and paying attention to the sea are also our choices.

In the era when the Earth was thought of as a plate, the sea was a huge waterfall falling along the round edge. When viewed from space, the shape of the sea was determined based on the edges of the land. In other words, the sea was drawn from the perspective of humans standing on the land and tailored to the shape of the land. We came down from the land and entrusted ourselves to the sea. We navigated the pitch-black abyss because we couldn't know its depth. What did the four artists see at the end of their voyage?

Last late summer, I lay on a bench at the Busan National Maritime Museum with artist Jung Da-jeong, looking at the sky. At that moment, it seemed she was looking at the sea drawn on a vast canvas, not the sky. Jung Da-jeong imagines the sea by freezing the sky in ice and walks far away until the vast sea fits into her palm. And she folds, bends, and sometimes makes tools to collect parts of the sea. She stretches out her hand and stirs the seawater. She records the sensation of seawater slipping between her fingers. She extends a bucket with a long handle and takes a sip of seawater. She folds the sea flat and when she becomes curious about the width of the sea, she unfolds it and throws a needle into it. The thread, swaying up and down along the waves to gauge the sea, leaves for the edge of the sea. The distant but close, close but distant sense of distance awakens the strange tension created by the Earth and the moon. When she listens to the story told by the thin thread on the paper cup telephone placed in the sea, the artist senses the looming ⬛. Jung Da-jeong's attitude tells us that the sea and we are loosely but firmly connected.

Artist Hwang Hyo-deok looked at ⬛ through the unit of breath, recalling memories of the scent of the sea. First, the artist wears a diving suit and enters the sea. Then, he circulates seawater in a tube. Upon reaching the deep ⬛, he converts the vibrations created by the movement of fish into sound using a hydrophone and emits them. The vibration is an indicator of the survival and vitality of fish. Through this indicator, the audience can gauge the breathing of the fish. The artist discovers that the fish in ⬛ hardly move up and down. Therefore, he created a buoy to control the up-and-down movement of fish and occasionally help them breathe. The audience experiences breathlessness by directly breathing with a buoy much smaller than human lungs. The breathless breathing conveyed by the artist is also the sound of life forms threatened by the foundations of life in ⬛. After diving in ⬛, the artist resurfaces and faces a lagoon. The lagoon is a place where the sea and land intersect and where seawater and fresh water meet. The artist records the moment when the breath of the sea begins and ends while looking at the lagoon.

The ⬛ encountered by artist Bae Han-sol is the terrain revealed when ship positioning technology tracks the actual location of the ship one step late or fast in the time lag. He began his work from an experience aboard a ship named "Beyond Trust." The artist tracked the real-time position of the ship he boarded through an application called "Marine Traffic," which shows the route and position of the ship. The artist watched the screen of the application, filled with numerous ships, but it was rare to encounter a ship even after a night had passed. The discrepancy between the actual position of the ship and its position on the application reveals the limits of modern technology in understanding the sea. The artist records a different sense of direction from the land in ⬛ where technical limitations are revealed. The land has fixed terrain, and traces remain from previous people. Through this, he finds the destination and direction. In contrast, the situation is different on the sea. For example, let's assume that we try to find our location on a small boat on the sea without seeing the stars and with a malfunctioning compass. Looking at distant rocky islands, cargo ships, airplanes, and comparing them with oneself, one might be able to estimate some direction and location. However, the objects for determining the position move away in each direction. Therefore, the ⬛ captured by Bae Han-sol indicates that our position is always relative, and if a center or focus is established, it is a temporary state.

Artist Son Yoon-won's ⬛ is a space inhabited by fish that have become objects of leisure or hobby. The artist prepares a dinner for them on a platter. While the term "platter" can be translated as a plate, it also refers to a dish that gathers desired food items. The platter filled with various flora and fauna may seem like a terrestrial paradise at first glance. Son Yoon-won borrowed the style of this platter from the 16th-century ceramics of Bernard Palissy (1510-1589). Adopting Palissy's style and decorating the platter by purchasing replica molds sold online is also a stance typical of artists dealing with sculpture. While opinions in academia may vary, Son Yoon-won viewed Palissy, who ended his life through religious persecution, as utilizing snakes as symbols of human desire based on the Bible. Therefore, the artist questioned whether it was valid for humans to anthropomorphize fish by placing snakes in the center of the platter, instilling fear in humans, although they are not harmful to fish. The eels and polychaetes, the food of fish, greet the audience outside the platter with a lively appearance, like fish filling the tank. The artist's prepared cool dinner is made of clay. Like the saying "return to dust when you die," the artist's dinner merely melts into small clumps of earth within ⬛.

Entering the indoor fishing cafe, one hopes that the fishy smell that touches the nose will occasionally remind the audience of their lives. If we could greet each other in 10, 50, or 100 years, the sea will be fine.